Music

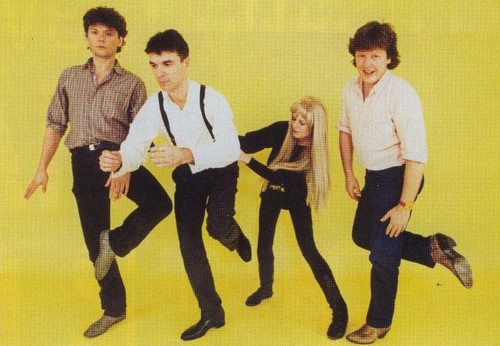

45 RPM: Talking Heads (Pt. 1)

This week sees the beginning of a new column at Heave, 45 RPM, in which Josh Watkins looks at the discography of a different band in detail every week. This week, Josh considers the Talking Heads. Part two will post tomorrow.

Talking Heads: 77 (1977)

I’d like to give some trite factoid about how this album was made, i.e. frontman David Byrne raised the money to record 77 by selling his father’s bones, but there are no such facts. This album literally just happened, and it happened in the perfect place – the CBGB punk scene in New York. On the surface, 77 fits in with Heads contemporaries Television and Elvis Costello, with sprinkles of funk and disco. Opening track “Uh-Oh, Love Comes to Town” is a mouthful of Motown bubblegum complete with steel drums and perhaps the happiest, grooviest bassline ever written on cocaine. A world music vibe floods “First Week…” with marimbas and a wacky sax in the chorus. Aside from this and the occasional piano lines, 77’s setup is two guitars, bass, and acoustic drums; Byrne’s love of synths and drum machines wouldn’t come for another few years. The guitar parts are twinkly and driving, Byrne and Harrison cleverly weaving together not unlike Verlaine and Lloyd shredding on Marquee Moon.

“No Compassion” is a tug-of-war of spacey blues-slide riffs and post-punky power chords and harmonics, and the song’s frequent changes leave you simultaneously scratching and nodding your head. Byrne as a frontman is wild. His delivery is direct, his words abstract, and paired with the music he comes off as a paranoid English teacher – his subtle anxiety culminates at the famed “Psycho Killer” and switches back to dweebish and optimistic in “Pulled Up.” 77 is masterful in its simplicity, a catchy hunk of clay that the Heads would later chisel into the Venus de Milo of art rock.

More Songs About Buildings and Food (1978)

Like Dracula, Heads fan Brian Eno materialized out of nowhere and ended up at the helm of the mixing console. His fangs still fresh with the blood of Roxy Music and Bowie, he entered the Heads’ lives to tighten their sound on More Songs, which is (as suggested by the title) an extension of 77 – but a version with its teeth sharpened. The white-boy funk influence is running at 200% here in almost every song. Frantz’s drumming was tightened to make each song even dancier than before. The guitars and vocals get a touch of reverb to keep up with the decade.

To this day, indie rock bands are ripping off the guitar dynamics in “Warning Sign” and the false stops in “I’m Not In Love.” So for the first eight tracks, we get a funkier, more concise 77 (including three of their best songs: “Thank You Heaven,” “Found a Job” and the bell-driven “Girls Want to Be With the Girls”). Enter “Stay Hungry” to change the rules, littered with key and tempo changes, reverse-looped guitars, crystalline synth layers and near-tribal drum fills. They follow this up with the molasses-slow Al Green cover “Take Me to the River (with similar traits), and then “The Big Country,” the album’s closer. This song plays between acoustic chords and a tripped-out electric slide guitar, while Byrne basically says “everyone in the South is ignorant and boring, but I ain’t mad.” These three tracks are slick, and lay some serious groundwork for the Talking Heads’ further experimentation.

Fear of Music (1979)

Off the bat with “I, Zimbra,” a chorus of gibberish over intricate afro-percussion, it’s apparent you’ve walked into a different circus. Here, the zebras are jangly and bloated (“Electric Guitar,” “Memories Can’t Wait”), the clowns fear the government but can’t stop dancing (“Life During Wartime”) and the ringleader’s voice echoes and slips away into the oppressive void of modern life (“Heaven,” “Drugs”). Fear of Music doesn’t love you, and even though it wants you to dance, it wants you to feel weird about it. Songs like “Mind” groove like an old Talking Heads song, but offer odd synth noises and reversed guitars on all kinds of spooky drugs.

“Cities” is in a similar predicament, still remarkably funkified and danceable but flooded with Byrne’s jittery shouting, dissonant organ smashes and what may or may not be the sound of tiny metal hammers. As with the previous album, the closing tracks stray the furthest from what we’re comfortable with in Headlandia. “Electric Guitar” slows down and stomps with a watery bass that sounds like synth imitating tuba and mechanical electro-shuffling. “Drugs” is, at this point, the most experimental song they’ve written yet – a floating Low-esque soundscape interspersed with bongo slaps and jagged guitar notes – and a perfect precursor to their most radical change.

Remain in Light (1980)

The sound of the 70s ending: polyrhythmic African drums, jiving chorus women, keyboards-for-horns, wiry high-range guitar noise, everything as percussion and tumbling repetition. How does “Born Under the Punches” even combine Afrobeat drums with funk slap bass, bleep-blorp computer noises and classic Talking Heads riffs? And then just sashay right into the stripped-down kitchen-counter percussion and Stevie Wonder keyboards, next combining ideas from both songs for the Afro-driven vocally intense “Great Curve”? The painstaking detail put into this album is what makes it so unrelentingly dense. It’s only forty minutes of music, but I can hardly ever listen to it in one sitting because there’s enough going on to give me chest pains. The first half of Remain in Light carries the same quirky optimism as most Heads songs, but more heavily percussed and intricately layered. It’s goddamn busy. The album’s latter half is the fistful of downers after the coked-out bonanza of the previous four tracks. Between the menacing funk uprise of “Houses in Motion” and the unstable howling drone of “Listening Wind,” you’re getting an alienating sound twice as cold as anything on Fear of Music.

True story: Byrne and co. had never heard a song by then-fresh band Joy Division, but did read a press review describing their sound. The group challenged themselves to write a song that fit that description and, lo and behold, closing song “The Overload” happened – the most crushing Joy Division song Ian Curtis never wrote. Remain in Light is a lot to swallow, but it was somehow the critical and commercial breakthrough the Heads were waiting for. Relentlessly poppy but experimental to an esoteric degree, this is when it all came together – the perfect way to kick off the 1980s.

Pingback: 45 RPM: Talking Heads (Pt. 2) | Heave Media()