Culture

SeePlus: “Backstory”

(Cover photo: From Ron Jude’s Alpine Star [2006])

Welcome to a recurring feature here at Heave, SeePlus, in which Chloe Stagaman helps you learn a little more about the Chicago art community every month.

It’s a Thursday afternoon and I have a meeting with Karen Irvine. Finally safe from the drizzle of rain outside, I enter the main gallery of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, schlepping off the last bit of raindrops from my purse. I have my recorder set to start, my notebook in my lap, and my program highlighted. I’m ready to interrogate the Curator and Associate Director of the museum in the most formal way possible.

But as Irvine descends the stairs into the gallery and introduces herself, I suddenly understand why my expectations for the day are borderline silly. She, like the exhibit encompassing her, is relaxed, warm, and confident. And so instead of a formal interview in which I demand answers and she hands them over, we walk together through the current exhibit, titled Backstory, and have a conversation.

The Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College is located at 600 S. Michigan Avenue. It consists of three levels, each white-walled with hardwood floors. Backstory presents the work of three artists who, despite being extremely different, all present personal bodies of work that have a specific connection to “place.” This “place” is manifested in many different ways—from the blunt images of pollution destroying a small town to a more abstract space that signifies the presence and absence of a lover.

The first floor of the museum is the largest, containing the main entry gallery with two smaller rooms extending off of it on either side. The floor’s division makes it the perfect space for Ron Jude’s trio of projects exploring the identity of his home state of Idaho.

It all begins in the leftmost, smallest room of the main gallery with Jude’s first project, Alpine Star (2006), for which Jude extracted photographs from his hometown newspaper The Star News. The photos, though small and very simply matted, ooze character. They are the talk of the town without words—a unique chronology of pictures haphazardly taken to accompany headlines. Irvine laughs along with me about the eeriness and bizarre qualities some of the photos possess. She also points out the repetition of a picture in the series, featured in the paper at different times of year. Back then, if you needed a picture, someone went out and snapped it. There was no searching in the records to make sure the photo hadn’t already been taken.

(From Alpine Star)

The simplicity of the first project barrels over into the deeper self-exploration of Jude’s second body of work, flanking the right side of the main entry gallery. Emmett (2010) is youth, memories, and experimentation. Through the experiences of an old friend, Jude manages to visualize the infinite feeling of adolescence. The photographs were all taken during the 1980s, when Jude was still figuring out his photography skills. Excluding their meaningful, often beautiful content, the photos are honest in their execution.

(From Jude’s Lick Creek Line [2012])

The first floor begins and ends with the photos in the main gallery, easily the most complex project of Jude’s trio. Lick Creek Line (2012) is a stunning lineup of photographs that juxtapose the idealized backwoods of Idaho with the destruction of development and heartless hunters. As Irvine points out, there is no real winner between old and new in this project. The two exist together in the space and compete for the attention of the viewer, but Jude neither condemns nor supports a side to the argument.

(From Lick Creek Line)

With that, we begin to make our way up to floor two, toward the work of another artist in the exhibition: LaToya Ruby Frazier. The second floor is small and could easily be labeled as the “problem child” gallery space. Despite limited wall space and office doors that interrupt the space’s fluidity, Frazier’s work takes over.

Honestly, it could take over anywhere.

The powerful, intensely personal nature of her photographs takes the exhibition’s themes of self and place to a new level. Frazier layers her life and relationships with the disintegration of the town and home around her in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Pollution, disease, cramped households: all of these subjects come to a forefront in these excerpts from Frazier’s 12 years of self-documentation.

Nestled into the second stairwell’s alcove is Self-Portrait (United States Steel) (2010), in which Frazier breathes in tandem with a steel mill releasing toxins into the air. Frazier’s blunt delivery takes full effect in this comparison, which eventually pushes us up to the third floor, the highest point of the museum and the home of the last piece of the Backstory exhibit.

Guillaume Simoneau fell in love with Caroline Annandale in Maine in 2000 at a photographic workshop. After the two had been traveling together for almost a year, the September 11th terrorist attacks spurred Annandale to decide to join the United States army. Her deployment to Iraq and the years that followed were a rollercoaster for the couple, who grew apart. Annandale eventually married someone else, and after her marriage failed she and Simoneau tried again, only to find that they were very different people.

(Guillaume Simoneau: 04 Canadian Marine jacket, Kennesaw, Georgia, 2008)

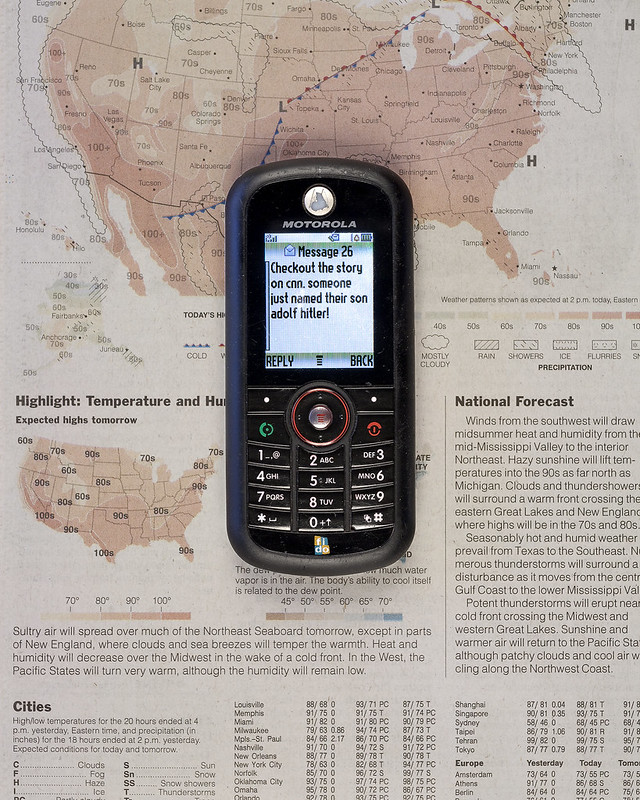

Love and War (2011) closes the Backstory exhibition with a non-chronological look into the destruction of their relationship, and the space that tore them apart. In this work, place is more of a point in time. Sometimes the two characters are together, other times they’re separated emotionally and physically. A ménage of photos, emails, letters, and text messages tells their tale. Irvine makes a point to tell me that although Simoneau’s photos are close together on the wall, they are not connected. There is a disconnect between each, so that they are stand-alone pieces that come together for the purpose of telling the story.

(Simoneau: 02 Checkout the story, January 2009)

And in three floors, the exhibit is over. As Irvine so eloquently describes, Frazier acts as a bridge from Jude (who is more occupied with space), to Simoneau (who is much more occupied with a personal narrative). The three distinct aspects of this exhibit work together harmoniously to generate a unique viewing experience that’s intensely personal and relatable. Everyone knows what it’s like to be in love. Everyone comes from somewhere. Everyone has been young and reckless. Everyone has a backstory.

The exhibit continues through October 6, 2013. If you would like to check it out (which you should!), MoCP is open Monday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Thursday 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., and Sunday 12 to 5 p.m.