Features

A History of Violence: Keef, Drill, and Chiraq (Part 1)

This is the first installment of Kyle Thacker’s essay on the musical history of Chief Keef, his connection to drill music, and gang culture in Chicago.

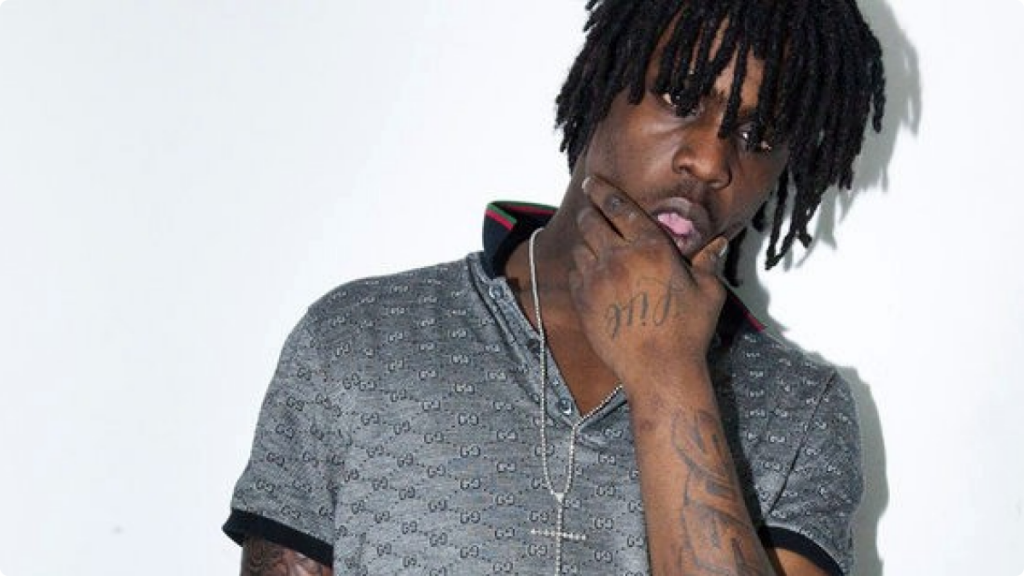

2012 was the year the match caught flame for Chicago hip-hop. The year Chief Keef leapt from local obscurity and fell into the national spotlight. Cheef Keef, born Keith Cozart, carried the baggage of a city ailing from gang-violence. 2012 was also the year Chicago saw a huge spike in murders, the most killings seen by the city since 2003. By 2013 his persona would become the scapegoat for this culture of violence and retribution, a culture well embedded into the barren neighborhoods of Chicago’s south and west sides before Chief Keef came along. Behind Keef marched a squadron of rappers performing “drill” music. New artists like Lil Durk and Lil Reese inked major label deals. Forbearer of the scene King Louie appeared on Kanye’s latest album. For better or worse, drill music artists had arrived.

It is now 2014 and two documentaries have been put out focusing on Chicago’s drill scene and the violent word these artists inhabit. In January Vice released the first two segments of an eight-part feature, Chiraq, which explore the links between gangland and the music inspired by this lifestyle. WorldStarHipHop (WSHH), the Wal-Mart of the hip-hop blogosphere, usually peddles cheap content to a huge following, but released a solid documentary, The Field, focusing on many of the same issues as Chiraq.

The violence illustrated in drill music isn’t any more shocking or explicit than themes rappers have been exploring since the late 80s, throughout the 90s, until now, with Chicago’s gang violence decreasing significantly since that time. So why is it now with Chicago that we can’t talk about one without the other? When did rap cease to be simply be an entertaining look at a world most don’t see, and one where the music had to be discussed in relation to the social ramifications it had for the neighborhoods it comes from?

The rise of Chief Keef (CK) started as ridiculously as possible. On the second day of 2012, a video was posted to WSHH that showed CK’s apparent biggest-fan-in-the-world deliriously freaking out over the young rappers release from jail. The video racked up millions of views and caused the viewers to scratch their heads and ask a pretty poignant question, “Who the fuck is Chief Keef?” The questioned prompted an answer from Fake Shore Drive, a blog that acts as curator and first contact for all things Chicago hip-hop.

The post featured a photoshopped mixtape cover of a then 16-year old CK standing shirtless and holding a handgun. The mixtapes most popular song “Bang” was one of CK’s first viral hits. CK’s grim aesthetic was set from this first video. “Bang” had a few hundred thousand views at the time of it posted to FSD, a solid but modest following based in the south side of Chicago. The violent tone was clearly set in the music and the visuals surrounding the music. But the cover art and music wasn’t much different than typical mixtape fair.

This post from Fake Shore Drive was on January 2nd, 2012. According to Chicago website DNAinfo, the first three murders of 2012 occurred on this day.

Flash forward two months to March and out comes an article written by David Drake for Gawker. The article is a great piece profiling Keef while he was on house arrest at his grandmother’s home in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood. The article’s headline claimed CK as “Hip Hop’s Next Big Thing.” The tone and focus of the piece was undoubtedly musical. There was even a long stretch of the piece that talked about the wild story of CK’s Japanese DJ and producer DJ Kenn, the man behind the beat of “Bang.” The side story of Kenn, a viable hip-hop love tale, details Kenn’s journey from his homeland of Japan to the USA in search of a career in hip-hop. He found it after being taken in off the streets by CK’s uncle. There was an inspirational vibe to the piece, how two kids who loved hip hop from across the world met, hustled, grinded and are now on the verge of fame.

Drake’s article had the compulsory mention of CK’s problems with the law, but it was only background work, the exposition building the mystique of a rapper climbing out of the trap life and dusting off his jeans before stepping into the national spotlight. More importantly, the mention of gunplay and arrests were specific to CK’s story as an individual, not as a marker of a cultural warzone.

March was one of the deadliest months for Chicago in 2012, recording more than 50 homicides. By the end of March 12th the city had recorded 83 homicides. By April 1st, there would be 120 homicides in the city, up sixty percent from the same date the previous year.

In April of 2012 we feel the unblinking eye of the national media shift focus towards Chicago’s gang problems. A piece from Huffington Post highlighted the 60-percent increase in murder rate from January 1st to April 1st. There isn’t any mention of drill music or Chief Keef. They do mention the usual suspects of potential factors for upturned violence – “lingering economic woes…high unemployment…unseasonably warm weather.”

The following month NPR ran a piece with the headline “Experts stunned by Chicago’s Soaring Homicide Rate.” This piece again mentions a “mild winter” as a reason, like murders being a casual symptom of weather like allergies. They also mentioned it may simply be a “statistical blip.” Again though, we have coverage of Chicago’s gang violence of 2012 without mention of the artists then blossoming from the same concrete those murders took place atop.

When did we reach the point we’re now at? Where the violence of this rap is something more than just a spice of narrative and exaggeration, or a report of the world these artists lived within. Now, like no other time, the entertainment we get from the music isn’t enough. We can’t separate the rapper from the statistics, and the hatred felt in these streets seems unconditional. And why is Chicago’s violence dealt with in the terms of warzones?

Chiraq. The name is catchy in a marketing sort of way, similar to Miller Lite’s Chicago-based “Chi-rish” campaign come St. Patrick’s Day. But is Chicago really deserved of the term? 2012 was a bloody and deadly year for the city. And by Chicago we mean specific neighborhoods in the city. It was the deadliest since 2003, the last year Chicago saw more than 600 murders. But 2012 was significantly less violent than the 90s were in Chicago. Still far too many murders, but what is the motivation and reasoning behind a name like Chiraq?

Pingback: A History of Violence: Keef, Drill, and Chiraq (Part 2) | Heave Media()