Culture

The Third Panel: This Is My Column! It Was Made For Me: The Spiraling Madness Of Junji Ito

Welcome to a new column at Heave – The Third Panel! Every other week, Alex dispels the myth that comics are only about superheroes by sharing comics books, graphic novels, and webcomics that are off the beaten path.

Writer’s Note: This column contains images of a very distressing nature concerning the human body and contortion; if you don’t like seeing the human body being warped in unrealistic and grotesque ways, please don’t click the links below!

Writer’s Note II: Because the comics featured in this article come from Japan, read them from the right to the left, as opposed to the left to the right.

Boo! Welcome to a very spooky Halloween edition of The Third Panel! Today, we’re going to be discussing horror comics because it’s almost Halloween, and because I really want to talk about Junji Ito.

So who’s Junji Ito? He’s a Japanese manga (literally “whimsical drawings”) illustrator who deals in images of body horror—that is to say, comics that remind us that our bodies are terrible factories that produce a lot of disgusting things that we pretend not to think about it.

The basic outline of most Junji Ito one-shots can be summed up thusly: Ito posits, “Hey, wouldn’t it be kind of scary if there was a town without any privacy?” or “Hey wouldn’t it be creepy if there was actually something outside that window you were always afraid to look outside when you were younger?” and then draws it in the most flesh-crawlingly realistic rendering you’ve ever seen. Incidentally, if you can look straight on at page seven of the second hyperlink without your mind physically reeling, I’m convinced you never had a childhood, or at the very least, you’re a braver soul than I am.

However, there’s more to Junji Ito than phenomenal draftsmanship—he’s really at his best when he’s tackling issues of obsession. Because in Junji Ito’s mind, obsession and warped bodies are two sides of the same coin—a physical manifestation of mental anguish.

Let’s take The Enigma Of Amigara Fault as our example. On the surface, it seems like a classic Junji Ito tale: an earthquake in an unspecified prefecture of Japan causes various silhouettes cut into the very earth to surface, and people begin to notice that the silhouettes correspond to them and them alone. This then promptes hundreds to make a journey to the fault to see their own holes, becoming obsessed with them and finally being driven by their own curiosity to crawl inside. But the story raises a fascinating question: the holes are a perfect preservation of you at that period in time, so what would you give up to preserve yourself forever? Would you give up your very humanity to do so? Stories like Enigma Of Amigara Fault are when Ito is at his best—the warped bodies are the products of warped minds, the physical punishment for crimes of obsession.

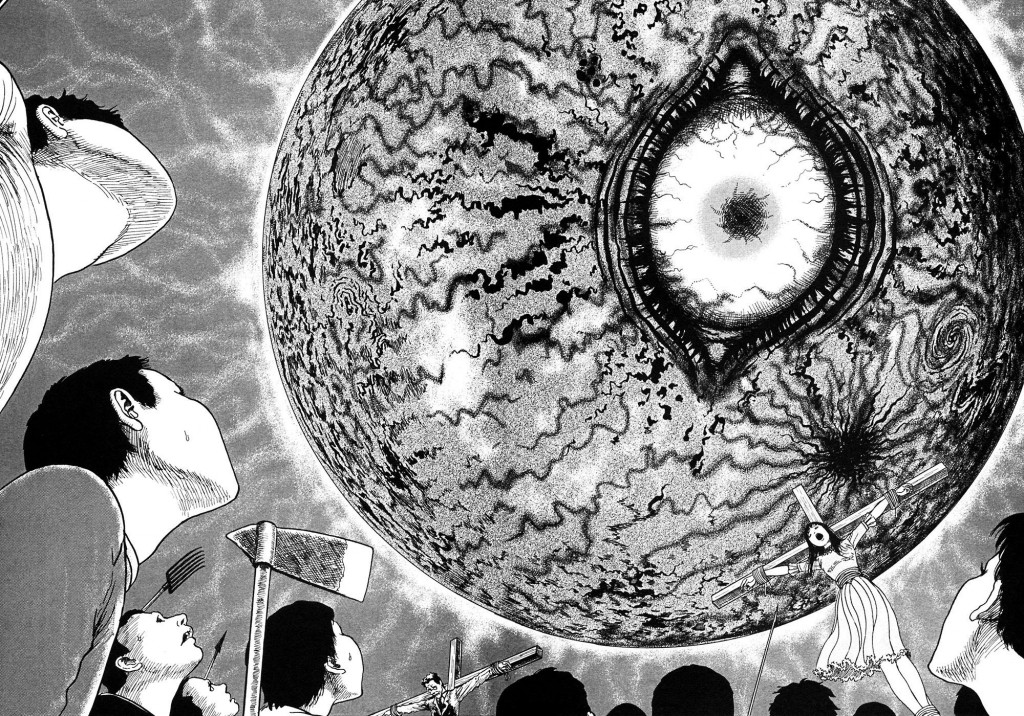

By far my favorite of Ito’s work is the three-volume series Uzumaki. Taken from a Japanese word meaning “spiral,” Uzumaki is the story of the inhabitants of Kurozu-cho, a small town in Japan that is cursed by spirals. The main characters are Kirie Goshima and Shuichi Saito, childhood friends whose very sanity is tested by the spiral obsession of their town. The first episode of the manga ends with Shuichi’s father becoming so obsessed with spirals that he kills himself by crawling into a sake cask in order to thrust himself into a more pleasing spiral shape, and it only becomes more grotesque from there. Great entry points into the manga (assuming I haven’t scared you off already) are “The Scar,” in which a girl’s childhood injury give her a scar that allows her to have any boy she desires, save one, which causes her scar to morph into a black hole capable of devouring anyone she wants but can’t have, “The Snail,” where a sluggish classmate of Kirie’s becomes quite literally that (okay so technically slugs and snails aren’t the same thing, but c’mon, you gotta work with me on the pun), and “The House,” where a mysterious skin disease begins affecting the residents of Kurozu-cho in the wake of several scar-based disasters.

Of course, it’s not a perfect story, and I find that the second volume of Uzumaki is the weakest, with its emphasis on surgical and maternal horror, but that does little to take away from the stellar last chapter, where Ito ties up all his loose ends into one giant take on cosmic horror that still makes my skin crawl a year after reading it.

Really, if there’s one reason I can recommend Junji Ito to you (aside from that he can make almost anything scary—even his obsession with his wife’s cat), it’s the fact that he does what a horror comic has to do to be scary in the best way possible—a comic can’t rely on jump scares to make you afraid. At a certain point, a comic has to stick to its guns and say “Hey this is really scary because you HAVE to look at it.” It can wait until you’re feeling ready to take in its full horror. And I say that knowing full well that as much as I hate the seventh page of “The Window Next Door,” I keep going back to it. I keep looking at it. It doesn’t outright scare me anymore, like the first time I scrolled down to look at it a year ago, but it still bothers me on a primal level, because it hits at something that terrified me when I was younger. And I’ll keep going back to that panel long after its initial impact has ceased. That’s the mark of something truly horrible—and truly brilliant.

Happy Halloween, everyone.