Culture

Ups and Downs: Thoughts on the bin Laden killing

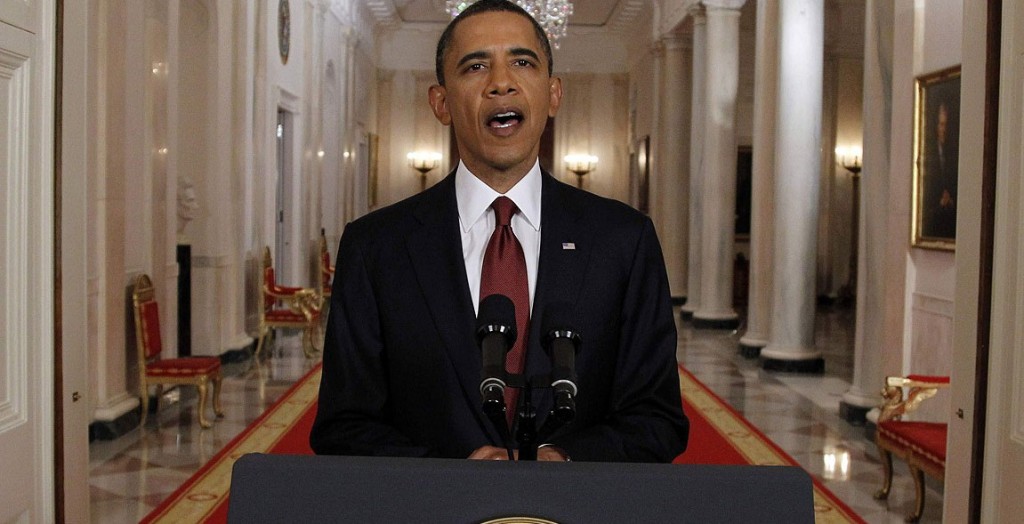

Up / Down: Osama bin Laden is killed by a U.S. army intelligence unit: Normally, I reserve this space for humorous observations on absurd news stories, but given the weight of Sunday’s announcement by President Obama that Osama bin Laden had been killed in Pakistan, it feels absurd to ignore the news. Like sporting broadcasts and reality TV programming interrupted to carry the President’s press conference, I think it’s fair to pre-empt the usual purposes of this column.

I’ve listed bin Laden’s death as both an “Up” and a “Down” not to overlook the significance of the event, but because my immediate feelings are decidedly more muddled than nearly everyone else I’ve spoken with since news of the Al Qaeda leader’s demise was made public. And indeed, the clear majority of Americans approached the news with joy approaching the revelatory. Crowds of people — from seemingly every background, faith and age — swarmed Time Square, the gates of the White House and other major city centers in impromptu celebrations which, with flags waving and citizens cheering, almost immediately brought to mind images of the days after the September 11th attacks, when mass displays of patriotism and professions of national unity were commonplace. More than that, watching the giddiness of people celebrating a major (and maybe I should have said this earlier, very justified) geopolitical assassination felt like watching a party stuck somewhere between campaign rally and Super Bowl victory. Maybe it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that the national anthem ceremonies before playoff games in the NBA and NHL on Monday were clearly charged with new energy. Or that on Sunday night, as the news filtered through Philadelphia’s Citizens Bank Park on smart-phones and in text messages during a Phillies – Mets game, the crowd began to chant “USA! USA!”

But where most celebrated, I feel mostly muted. It’s not that I find the news or the reaction repulsive; indeed, for as disconcerting as it is to see masses of people celebrating the death of a man, I’m no pacifist, and my knee-jerk liberalism aside, I don’t see how you can see this as anything but justified, if not justice outright for all the rubble, ash, broken bodies and broken families of September 11th. Too much of the debate — online, in print and on television — is dictated by the intervening decade, in which the spectre of two wars (one illegal, one just ill-advised and mismanaged), and the suggestion of a never-ending battle against “terror” color our reactions.

Despite this great bit of commentary from NPR on whether it is really ethical to celebrate the murder, albeit justified, of a man so publically, I think there are certain things we shouldn’t forget: Osama bin Laden was a mass murderer, responsible for planning not just the September 11th attacks, but also the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen and, allegedly, a 1996 bombing of a Khobar military complex in Saudi Arabia. Bin Laden was a sadistic and callow man with enough blood on his hands to last lifetimes. I don’t feel like crowding the streets to celebrate his death, but I think I at least understand the urge.

But we shouldn’t ignore the consequences — or fail to question the real-world significance — of his death, either. Al Qaeda, no doubt, was and still is dangerous, the 2004 bombings in Madrid should be proof enough of that. Still, as a number of news outlets have since pointed out, bin Laden’s role in the organization was largely administrative, modeling the CEO of a company who approves decisions more than someone involved directly in the planning of any attack. In terms of how U.S. and international intelligence agencies analyze Al Qaeda, many high-ranking men in the terrorist organization are still at large, making bin Laden’s death (and his life for the last decade) essentially symbolic.

But Rachel Maddow and NBC’s Richard Engel, who is probably the best foreign affairs correspondent in any U.S. news organization, did a great job of pointing out that symbols are important, and any damage done to the franchise image of Al Qaeda also damages the mythology with which bin Laden and the group sold themselves (skip to the 8:40 mark of this clip for Engel’s commentary):

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

More importantly — and, again, often lost amid the myriad ways that the memory or image of September 11th has been invoked to justify wars, elect candidates or sell cars — is that for many people, bin Laden’s death, symbolic or otherwise, has personal significance. For those that had to watch loved ones fall or jump from the World Trade Towers, or burn up in a scar across a field in Pennsylvania, bin Laden’s death must have a weight that’s nearly impossible to articulate. Does justice or retribution carry the same importance or visceral appeal ten years after the fact? To be honest, I don’t know. But I think that those who had to mourn private loss amid public spectacle deserve at least the space to respond to the news as they will, whether with jubilation or resignation.

And what of the hundreds of thousands of U.S. Muslims who had their religion hijacked from them by bin Laden and other radicalists? For Americans of Middle Eastern descent who have endured 10 years of violence and discrimination and suspicion, who live in a country where it is a political liability for the President to have the middle name “Hussein,” and where politicians proudly campaign against building a Mosque anywhere near ground zero in New York, the day must have some meaning. Indeed, in Dearborn, MI, where the largest number of U.S. Muslims live and where, just last week, thousands gathered to protest demonstrations by Terry Jones, the Gainesville, FL pastor now infamous for burning a Qu’ran, citizens gathered again after bin Laden’s death. As this Chicago Tribune article notes, most of them expressed relief and hope that the national perception of American Muslims would change.

For all these reasons, the death of Osama bin Laden should be something positive, right? But still, I cannot shake lingering questions and thoughts that others seem eager to gloss:

1. President Obama made it clear that the Pakistani government played no role in the attack that killed bin Laden, and were not even notified of the fact that it was taking place. Moreover, the compound in which bin Laden was killed (and may have lived for up to six years) was in Abbottabad, a north west and affluent suburb of Pakistan, less than a mile from where the Pakistani government trains recruits for its intelligence agency. Can you imagine the outrage if the most wanted man in the world were found to be less than a mile from West Point Academy, for example? In 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton directly accused members of the Pakistani government of knowing where bin Laden was hiding, and this does nothing but underscore the issue. Where does this leave our political relationship with Pakistan, a country that is has received more than $10 billion in U.S. funds to help prosecute the “War on Terror”?

2. Speaking of money, I would love to see someone or some group evaluate exactly how much money was spent over the course of nearly ten years to catch one man? Many people took the news of his death as proof of American perseverance, but it seems to me that it can just as easily be read as evidence of protracted failure or miscommunication. How does the world’s most advanced military power justify taking a decade to find a single human being — one who never traveled out of the very region in which he was always believed to be hiding?

3. Rightfully, many people have expressed gratitude and appreciation for both the troops that were directly involved in bin Laden’s killing, and for the sacrifice made by U.S. service persons and their families everywhere. Don’t forget that the news of bin Laden’s death potentially puts active-duty servicemen at greater risk, as CNN reported that all military bases and personnel in Afghanistan were on red alert. Families who have loved ones deployed overseas met the news in a more subdued manner than the whooping crowds outside the White House.

4. To that larger end, what kind of retaliation can be expected, either overseas or at home? Any celebration needs to be tempered, to some degree, by that thought, right?

5. Lastly, how long do these impromptu displays of patriotism and emphatic declarations of “unity” really last? We like to tell ourselves that we see the best we can be in the most pressing and difficult times, but how long before the news is again dominated by the numbing bullshit of birth certificates? What’s a better indicator of the quality and character of our nation — the brief moments of nonpartisan thought that too quickly evaporate, or the avalanche of vitriol that embeds itself into almost everything we do and say?

So, in the end, I suppose it is not that I don’t know what to feel about the death of Osama bin Laden, so much as it is that I find myself lacking a way to really articulate how many different things I feel: reactions both visceral and more rational interwoven in the complexity, uniqueness and confusion of the situation.

Your thoughts?

Pingback: Reality TV stars tweet about bin Laden’s death – Examiner.com | BigBoring.com()